New Zealand museums need neutral organisational viewpoints and stronger science

Publicly-owned museums enjoy public support—tax-payer (or rate-payer) funding and high visitation—only while they are trusted and respected. To preserve trust, museums must be politically neutral. Institutions such as museums and universities can maintain a degree of political neutrality by being a forum for ideas and discussion, rather than a protagonist in debates.

New Zealand is too small for separate natural history or ethnographic museums. Instead, the four largest museums (in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin) are encyclopaedic general museums where science (natural history, e.g. botany, zoology, geology) and culture (human history, e.g. ethnology, history, applied arts) must co-habit. Among their duties these museums must prominently promote their science half. Science museums (and therefore the science part of encyclopaedic museums) have “an ethical responsibility to safeguard scientific integrity” and need “loyalty to facts and evidence.”

Politicisation of museums

New Zealand museums have increasingly embraced identity politics. This is evident in many museum planning documents. Future Museum, Auckland Museum’s 2012 “strategic vision”, for example, includes two major policy documents, He Korahi Māori: a Māori Dimension, and Teu Le Va: Pacific Dimension. The latter offers “pathways of acknowledgement and inclusiveness” within the museum, based on the idea that “Pacific people have a special place in Aotearoa.” No other ethno-cultural groups get their own guiding documents.

He Korahi Māori ensures a Māori dimension in “all of the museum’s plans and activities”. What might this mean? It is hard to imagine a Māori dimension to an exhibition of English pewter or Chinese porcelain, when pre-contact Māori society had no metals or pottery. Importantly, He Korahi Māori overlooks that specific cultural dimensions have little relevance to science in museums. This is because the scientific method serves to overcome the limitations of local cultural perspectives by inviting criticism from everywhere. There is only one version of science, which is universal and understood internationally. Investigations or findings are either science, open to any informed criticism, or not science. Science has no shielded local or cultural varieties. Despite Hitler and Stalin, there is no “Aryan science” or “communist science” with special bodies of protected knowledge.

Many museum planning documents push a particular view of the Treaty of Waitangi, and any perceived principles of the Treaty are political. The original 1840 “Articles Treaty” can be distinguished from the recently-developed “Principles Treaty“. The contemporary reinterpretation of the Treaty as a “partnership”, favoured by the political Left, is contestable. Former Labour prime minister David Lange stated: “The treaty [of Waitangi] cannot be any kind of founding document, as it is sometimes said to be. … The Court of Appeal once, absurdly, described it as a partnership between races, but it obviously is not”.

Auckland Museum’s administration now talks about challenging “colonial narratives” and making the museum “tikanga-led” (led by Māori culture, values and knowledge). I checked word-counts in the two most recent annual plans of Auckland Museum and annual reports of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Wellington). All four documents show the same pattern: culture is privileged and science marginalised. The word “science” appears 0–5 times in each document and science words like zoology, botany and archaeology get 0–2 mentions. Meanwhile, the documents are swamped with cultural key words: Māori (44–81 mentions per document), iwi (= Māori tribes, 16–43), culture (9–37), mātauranga (= Māori knowledge, 7–26). Te Papa’s recently-developed natural history exhibition gives further signs of ideological positioning.

Te Papa’s natural history gallery

In tandem with their large natural science research collections, museums provide secular space for major long-term natural history exhibitions presenting evidence-based explanations of the natural world. These exhibitions contribute to a world-wide intellectual movement to advance science, a mission bigger than, and different from, parochial political or cultural concerns. Museums may mount temporary exhibitions with different disciplines combined for special effect, but core, long-term galleries generally cover single broad subjects.

Te Papa disrupted this traditional arrangement, when in 2019 it unveiled a new principal natural history gallery (Te Taiao / Nature). Instead of devoting Te Taiao / Nature exclusively to science, as in the natural history galleries it replaced, Te Papa incorporated Māori cultural material throughout, to contrive a novel science-culture gallery. Spiritual beliefs now sit alongside scientific knowledge. To be clear, it is thoroughly appropriate that museum displays cover mātauranga Māori. My objection is to the shifting of the Māori view of nature from ethnographic galleries (Te Papa has two permanent Māori galleries) to science galleries. I question the asymmetry whereby human history galleries continue to present just culture, but science galleries now get one local cultural system mixed in with universal science.

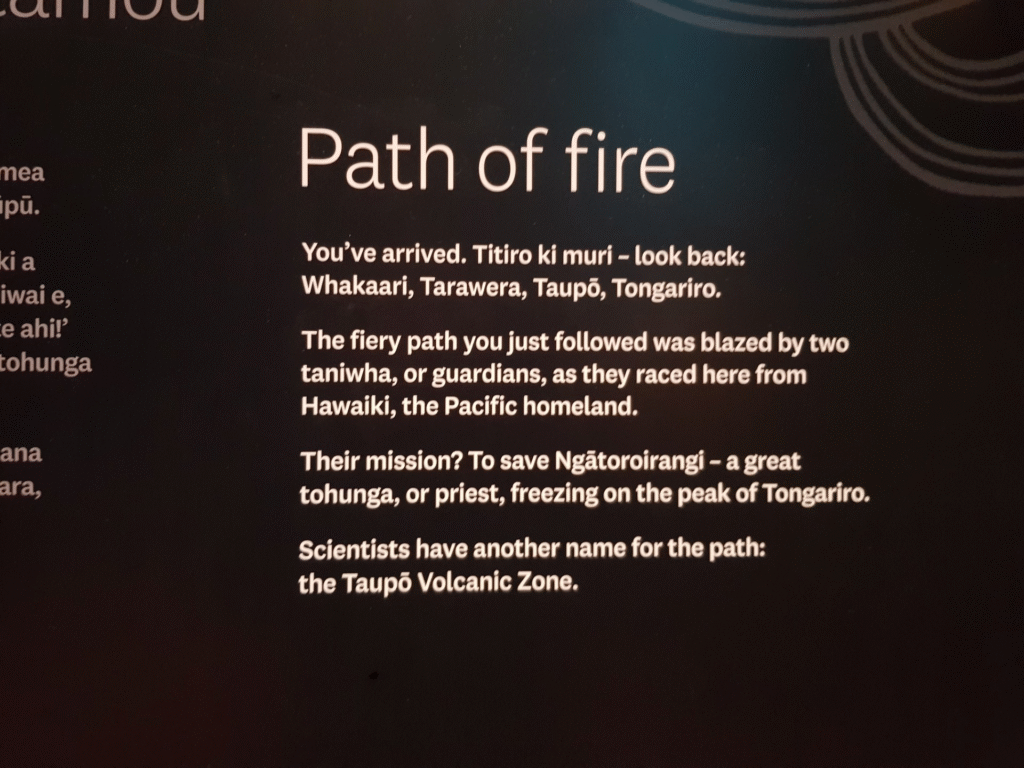

Te Taiao / Nature is a new “nature and environment zone” that explains the natural world “through mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) alongside science”. Exhibition developers refer throughout to the demigod Maui, who “can shapeshift into a bird, a lizard”. “He helps us understand the nuances of Te Taiao [nature] from a Māori perspective.” The Māori view of nature makes no distinction between nature and culture and includes mythology and spirituality (Roberts, M. Auckland Museum Annual Report 1999–2000: 45–47). So, labels in Te Taiao / Nature state, for example, that the jostling of tectonic plates is “the shifting of Ruaumoko, god of earthquakes”. A “mauri stone placed by a hinaki [eel trap] kept eels thriving”. The creation story of Maui fishing up the North Island gets a mention.

Museums need to maintain academic standards but Te Taiao / Nature makes a category error. Mātauranga Māori is the counterpart, not of science, but of the folklore about nature that all societies around the world developed from their beginnings. Modern science emerged before and during the European and North American Enlightenment, transcending local folkloric explanations of the natural world and becoming an international system. Mixing parochial mātauranga Māori and international science may confuse visitors and undermine young people’s developing understanding of science. Local academics have recently noted, for example, that science and mātauranga are “intrinsically contradictory approaches to knowledge that resist both combination and interrogation of one by the other” (Anderson, A. 2021, [Letter to the editor], Listener 277(4211): 6–7) and that placing science and indigenous knowledge alongside each other “does disservice to the coherence and understanding of both” (Ahdar et al. 2024, World science and indigenous knowledge [letter], Science 385(6705): 151–152). Putting a system that depends on unrestricted openness to criticism, as if on a par with a system that depends on protection from criticism in the interests of faithful transmission, is problematic.

By putting the Māori view of nature in the single science gallery, Te Papa seems to promote the postmodernist ideas that there are no universal truths and that all knowledge is culturally derived. This confused and simplistic ideology seeks to undermine science and other narratives construed as Eurocentric and colonial. Te Taiao / Nature implies by its mixed content that science is unremarkable—just one of many equivalent world views—and that indigenous “ways of knowing” are somehow equivalent to science. By shrinking its science contribution in this way, Te Papa wavers from its truth-seeking mission.

Risk to reputation

Until recently, science remained unaffected by postmodernism, an ideology that many consider has damaged the humanities. The imposition of postmodern views in the science sphere is a serious concern that scientists must oppose (Krauss 2024, Alan Sokal’s joke is on us as postmodernism comes to science, Wall Street Journal).

To protect their public credibility and reputations, here are three suggestions for New Zealand museums: 1. Regain political neutrality in your organisational viewpoints. 2. Restore science and science thinking to its equal place as a core museum component alongside culture. 3. Maintain or restore science galleries, which by definition can present only knowledge, not a mixture of knowledge and belief.

Museums could choose to continue traditional pride in the universals of science and world cultural heritages alongside increasing support for the renaissance in Māori culture and knowledge. This does justice to all and minimises reputational risk. They should avoid the fashionable politics of aggrandising one while playing down another. Making science exhibitions share space with cultural content, and challenging “colonial” narratives, is risky. If politicians, donors, and the visiting public tire of a bias of culture over science, then visitation and funding may be threatened.

Brian Gill has a PhD in zoology from the University of Canterbury. He was Curator of Land Vertebrates at Auckland Museum for 30 years. Brian publishes in ecology and palaeontogy and has undertaken field-work in New Zealand, Australia and Pacific Islands.]